By Victor Angula /

Okongo is one of the smallest local authorities in Namibia, an urban centre so small that it is run by a village council.

The small town is 99 kilometres from Eenhana along the road to Nkurenkuru, the regional capital of Kavango West region.

Omutumwa travelled all the way from Oshakati, through Eenhana, to Okongo just to assess the situation of shack dwellings in Okongo.

While the town is so small that one can walk through all its streets just in one hour, the one remarkable feature about Okongo is that it is a clean place. And the situation of informal settlements is not very serious.

In fact there is not one informal settlement. All the shacks one sees are built on demarcated plots, some of which are already fully serviced and provided with water and electricity.

Omutumwa went first to the offices of the Okongo Village Council, which are situated quite a distance away from the main road.

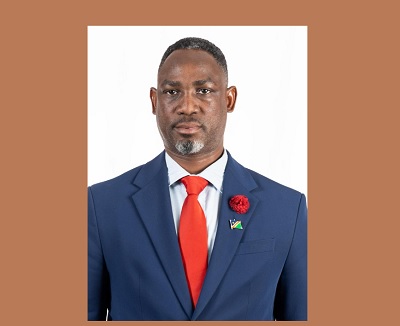

The Chief Executive Officer of Okongo Village Council is Mr Immanuel Haikali. Soft-spoken, Haikali says that the village council has a proactive approach on land delivery.

He states that the council has a waiting list, of which the waiting time depends on the availability of funds and land, but only he couldn’t say how long the list is currently as “it needs to be updated”.

“This year we are lucky, we will compensate the owners of two fields,” says Haikali. “In the next financial year we will allocate land to low income earners, those with no permanent jobs and vendors. These are mostly the people we cater for at New Reception.”

New Reception, also known by its residents as “Unam Location”, is the part of town where housing structures made out of corrugated iron sheets are found. This used to be Okongo’s informal settlement when the village council was established in 2015.

Before 2015 Okongo was just a settlement, run by the Ohangwena Regional Council.

Unam, which has some 1000 housing structures, no longer fits the description of “informal settlement” since most of it has been formalised and a lot of its residents have managed to turn their shack houses into brick houses built at the standard of the town.

Haikali states that meeting the demand for land quickly as the population of the town grows, in order to prevent the growth of slums and disorderly shack dwellings, is a priority for the village council.

“We are not here to serve ourselves, or serve the council, but to serve the people. Our mandate is to provide local authority services. So we are trying with the little we have.”

Now the village council is working on their plans to create a new township that will have more than 700 plots to cater for those who are on the land waiting list.

“This new township is already planned, and surveyed. We are only waiting for approval from higher authorities.

“Everyone can buy title deeds. Everyone will be staying at their own plot, well demarcated plots, with roads, services already like water, except for sewer. Those willing, can set up septic tanks to have individual sanitation. We don’t have communal taps.”

Okongo also has a feature that is unique and unlike other towns – it draws its water from the ground and supplies the water to its residents.

“We have our own boreholes and water wells. We do testing every six months to see if the water is still fit for human consumption.”

Meanwhile, as a small town, Okongo’s residents face the challenge of income. Although the village council is quick to provide land, the challenge lies with residents to build permanent structures on their allocated land.

This challenge is magnified by Ms Linea Ruben, a 38-year-old educarer who owns a day-care and kindergarten at Oshapopi Location. Ms Ruben who has been an educarer for 9 years says that she has been operating her day-care without enough support from public institutions.

The day-care was operating from someone else’s house, but after Covid-19 the owner of the house was reluctant to allow the day-care to reopen and resume operations.

“Twice I went to the village council asking for land, and I was allocated this plot in 2021,” Ruben says.

She set up a corrugated iron sheet structure which serves as the day-care and kindergarten, and also the accommodation quarter for herself and an assistant teacher.

“As of this year we have 26 kids. During Summer it is hot, and during Winter it is cold,” she states.

“We have no electricity, and our water was closed some months ago. The solar panel we had was stolen after someone broke into our place during a holiday.

“The income we make is not enough. The parents, out of ten only two are committed to making regular payments for their kids. We are doing this just for the love. The Ministry of Gender, Poverty Eradication and Social Welfare says that we cannot send away children of parents who are not paying since every child has a right to education.

“We have desire for educare, which is education and healthcare provision, but we just kind of volunteer. We are getting no benefits, no income from it, and we are getting tired.

“It is getting tough day by day.

“We try to go forward but situations of lack of income keep pulling us back. Sometimes we want to make a decision to develop the day-care, to build proper structures and move from the shack, but we have to make a choice between eating or buying bricks and cement.

“The quote we got just to build a septic tank was N$12,000. We can’t afford it. Sometimes it discourages us.

“Kids keep breaking the chairs, so that some now sit on empty beer crates. We don’t even have a proper chalk board.”

Ruben’s desire is for the government to consider the importance of the work which day-cares and community kindergartens are doing for the nation, and treat them as deserving of continuous support as they do with public schools.

Lack of income is the most serious challenge in Okongo, a situation which the village council is aware of. Ruben says that they pay a monthly fee to the village council of as little as N$70.00 for their day-care plot.

While the Okongo Village Council is committed to providing land to residents in response to the growing population, the challenge lies in how residents can find ways and means to build proper structures on their pieces of land for residential, institutional and business purposes.

In the photo: Okongo is an emerging town in eastern Ohangwena Region. In another image is day-care and kindergarten owner, Ms Linea Ruben, during the interview with Omutumwa’s reporter Mr Victor Angula; and the shack which serves as a day-care and kindergarten for 26 children in Oshapopi, Okongo (photos by Olivia Anghome).

[NB. This article was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Omutumwa and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.]